This article is part of a Sifted series exploring European tech’s relationship with the Gulf.

Date trees line the roads in Al Ain, an Emirati city on the border with Oman. The area is greener than the rest of the country, thanks to its coveted supply of groundwater.

It’s here that a team of scientists are working on using algae to capture carbon dioxide: a technology that could, if they can scale it up, make some kind of a dent in the UAE’s significant carbon emissions.

The project is run by UK-based Cyanocapture — one of several European climate startups that have headed to the UAE to deploy their tech.

The Gulf’s future is intrinsically tied to climate change. The already arid region is heating up at a rate twice as fast as the global average – and the flooding that hit Dubai last month crystalised the threat of a changing climate and more extreme weather events. At the same time, there’s an acute awareness that the region needs to build a post-oil economy.

All that is leading European climate tech entrepreneurs to set up shop here, building businesses around everything from bioreactor-cultivated meat, to CO2 sucking algae systems and giant towers that could cool the air with seawater.

Harnessing algae

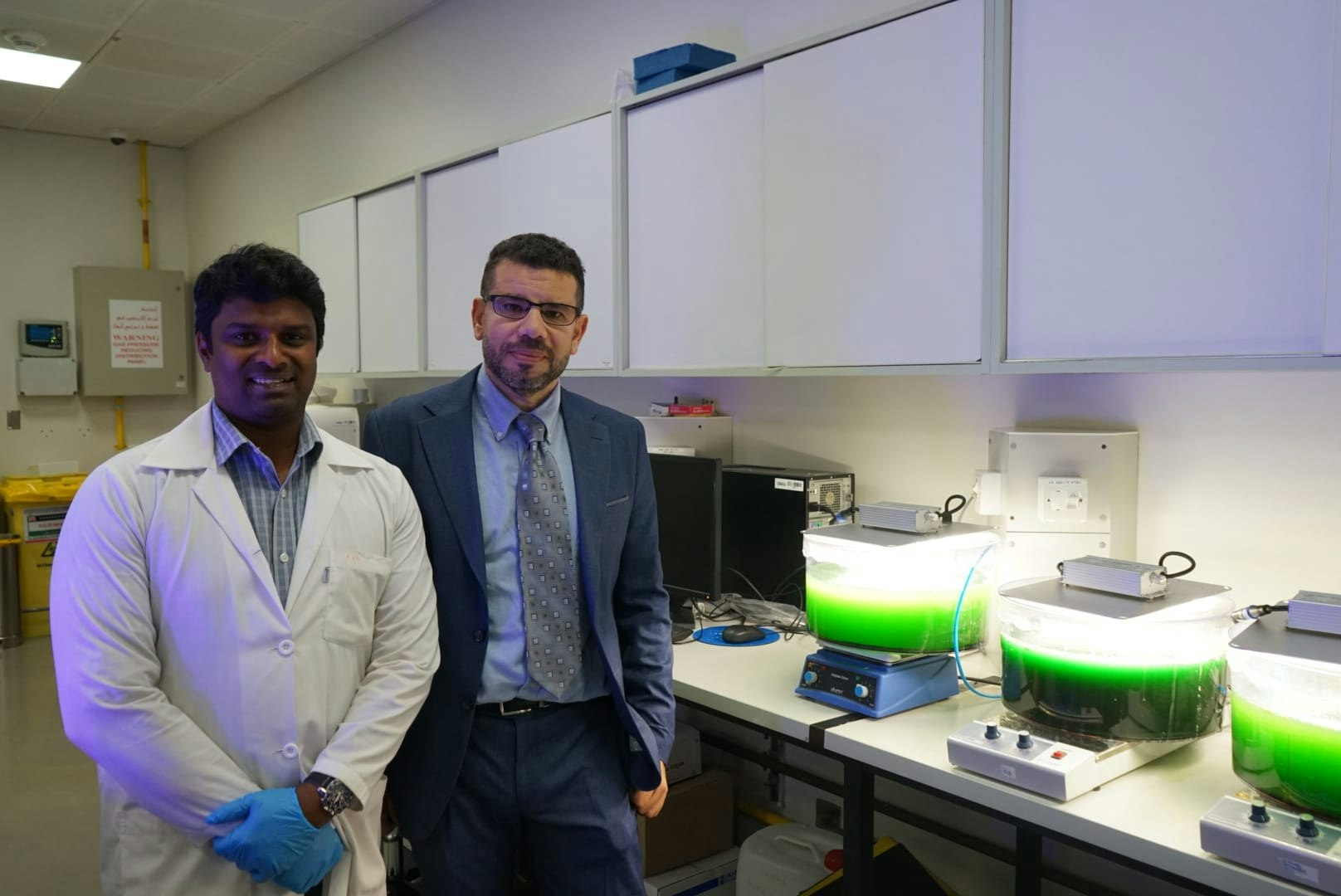

Cyanocapture, which in 2021 received a boost from Elon Musk’s XPrize for carbon removal, is working with scientists from United Arab Emirates University in Al Ain to develop a system where algae sucks in the carbon produced by industries like cement manufacturing or power stations.

“Algae captures carbon dioxide better than plants,” says Dr Pratheesh Prakasam. The team is using a variety that grows fast in high temperatures. The algae sits in tubes and has air pumped over it, sucking in CO2 as it grows.

The UAE is an ideal deployment site, says fellow scientist at the company Dr Ashraf Aly Hassan. “To grow as many cells as possible, you need a lot of sunlight. The optimum conditions for algal growth for carbon dioxide uptake are here.”

Cyanocapture’s system continuously circulates new algae into the tubes and takes out algae that has reached maximum growing capacity. The old algae is then turned into biochar — a stable form of carbon which can be buried underground or used to improve the quality of soil.

The oil majors

Other European climate companies working in the UAE include Cambridge-based startup Levidian, which secured backing from Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund Mubadala.

Levidian’s tech takes methane — a potent greenhouse gas — from landfill, wastewater, or oil and gas sites, to produce graphene, which can be used as a building material, as well as in batteries.

“The Middle East has lots of landfill that’s not been treated, lots of oil and gas, where there are hydrocarbons to strip the carbon out of, and it also has lots of heavy industry, which is where we can help,” says Levidian CEO John Hartley.

“As a strategic focus for us, there is a real political will, particularly for the UAE, to be a leader in clean tech, but also in graphene production.”

Levidian’s tech produces hydrogen as well as graphene. The UAE is on a drive to position itself as a key producer of low-emission hydrogen: a fuel which it sees as a central to its post-oil economy.

Levidian now has three people on the ground in the UAE and a partnership with ADNOC, the Abu Dhabi state oil firm.

“Levidian believes emissions reduction will happen fastest when the existing system is decarbonised using existing infrastructure,” says Hartley. “Gas production won’t stop any time soon and in the meantime, Levidian’s technology offers a practical, immediate solution to decarbonising gas processing facilities.”

He points out that post-oil, sewage waste and landfill water will exist at scale: both of which produce methane and Levidian can use to produce graphene and hydrogen.

Living sustainably in a desert

Most of climate tech funding goes into mitigation technologies (those which prevent or remove emissions from the atmosphere). The other side of the coin is adaptation — tech which can help communities live in a changing climate. In the Gulf, that’s a pressing need.

One European entrepreneur working on that problem is Paul-Emmanuel Hervé, cofounder of Atmocooling. Hervé and his cofounder Paul Mahacek are building the company in Abu Dhabi, working on tech that can cool the air.

The company — which is backed by UK-based Founder’s Factory and Unruly Capital, also based in the UK — has developed a nozzle that sprays sea water (a resource the UAE has plenty of) from the top of 20m towers onto the ground.

The nozzle spits out water droplets of a particular size. It makes sure there’s the right amount of water to evaporate and produce a cooling effect, and that the salt in the water lands in a trough in front of the towers, rather than spitting out onto the land and changing the composition of the soil.

Atmocooling says that its tech can lower the temperature of air by 15 °C. It can be used to cool urban areas, reducing the energy needed for air conditioning, and in solar panel parks: panels work less effectively the hotter they get. It could also help desert land into farmable land, once scaled up.

Vertical farming’s opportune market?

Also working on the pressing issue of food security in the Gulf is Scottish startup IGS. In Dubai, it’s working on one of the world’s largest vertical farms, in conjunction with UAE-based Refarm.

Vertical farming — where crops are grown under artificial light in racks — has had a rocky time of it lately: with numerous high profile companies going bankrupt, many of which were deploying their tech in Europe.

The Gulf makes sense for the industry, says IGS CEO Andrew Lloyd, given its reliance on food imports (around 85% comes from outside the country) and the availability of cheap solar energy to power the farms, which have struggled due to rising energy prices.

IGS is building a 83k m2 “gigafarm” which could produce up to 3m kg of produce annually. It’ll produce food directly for customers as well as growing seedlings for farmers, helping to get crops started and give them a better chance of survival.

IGS has two demonstration towers up and running in Al Quoz, an industrial neighbourhood in Dubai. The project will use water derived from food waste: the region is facing water shortages and, although desalination projects are underway, producing food using recycled water is a big win for its sustainability credentials.

The other European food tech sector looking at the Gulf is the cultivated meat industry. Countries in the region import 62% of their meat.

UK startup Ivy Farm, which is working on growing meat in bioreactors, says it’s looking to export its tech to the region and its team recently travelled to Riyadh for talks.

The megaprojects

Climate tech founders say they’re drawn to deploying in the Gulf because of the size of projects being worked on here.

“There is an interest in ideas that are big and impactful,” says Levidian’s Hartley. “They think very big, they’re less interested in small things that will make a marginal difference.”

Einride, a Swedish unicorn which develops electric trucks, is also working on a project in the UAE, and praises the scale on which the country thinks. “I love the ambition here, they understand that the future needs ambition,” he told Sifted. “The economies of scale will be happening here first.”

Megaprojects like Saudi’s The Line — a 170km glass-walled city set to take shape in the country’s desert — are looking to snap up climate technologies, be it next-generation travel tech or food technologies.

That said, many climate activists will question whether the Gulf’s rush to adopt environment hacking tech at scale will make a difference, as the region continues to pump out large amounts of oil and gas.

For now, a steady flood of European climate tech startups are making the journey over to the UAE. What happens to that dynamic should the country manage to develop more of its own home-grown intellectual property, remains to be seen.

Read the orginal article: https://sifted.eu/articles/european-climate-tech-gulf/