Banks on the shields yesterday in Piazza Affari, driven by the increasingly concrete possibility that a newly established European bad bank could buy en bloc all the impaired loans that are on the books of EU credit institutions or that will arrive there, because of the crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Banks on the shields yesterday in Piazza Affari, driven by the increasingly concrete possibility that a newly established European bad bank could buy en bloc all the impaired loans that are on the books of EU credit institutions or that will arrive there, because of the crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic.

An article published by Il Sole 24 Ore reported that on 25 September the subject will be at the centre of a roundtable organised directly by the European Commission, in particular by Dg Fisma, the Directorate for Financial Stability and Capital Markets responsible for EU policy on banking and finance. The meeting will be attended by the vice-president of the EU Commission, Valdis Dombrovskis, the chairman of the Econ Commission, Irene Tinagli, the head of DG Fisma, Klaus Wiedner, as well as officials from the ECB, SSM and EBA and representatives of the various national asset management companies (for Italy AMCO is involved, led by Marina Natale). The news was confirmed to ANSA by a spokesperson of the EU Commission, who reiterated that Brussels is “developing a comprehensive strategy on non-performing loans”.

The hypothesis returns to the market periodically. It was January 2017 when Andrea Enria, then president of the EBA, called for the establishment of a management company at European level, which could deal with the mass of impaired loans that burdened credit institutions in the EU area. Enria’s project, however, did not go ahead because it clashed with the regulations on bail-in banking.

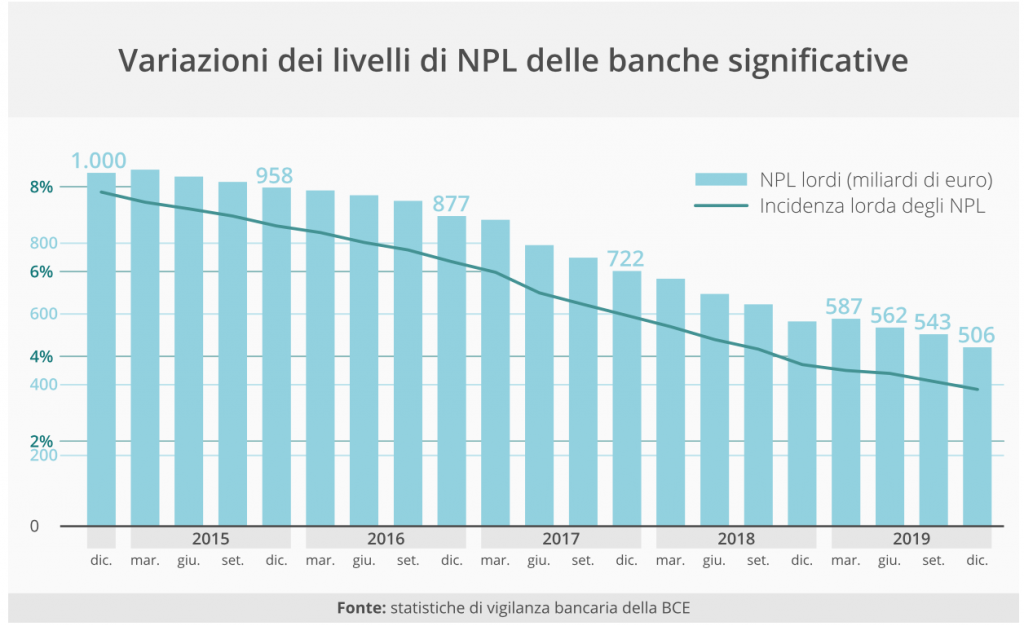

In recent months, however, the international press has reported new arguments on the subject from the European Central Bank. In particular, the Financial Times reported in April, while Reuters returned to the subject in early June. The fear is that the lockdown crisis could bring back to the levels of 5 years ago, at one thousand billion euros, the European amount of impaired loans, which today has fallen to around 500 billion euros. The project under discussion implies that the bad bank could issue bonds that could be bought by commercial banks in exchange for the contribution of NPL and Utp portfolios. The banks, in turn, could use those bonds as collateral in their financing operations with the ECB. But the scheme inevitably clashes with the positions of countries such as Germany, which have always been reluctant to plan for shared responsibility for the debts of other countries, although it has been seen that on the Recovery Fund issue its position has become much more relaxed.

In any case, the crucial point remains that of the price at which the bad bank should buy the impaired loans, which on the one hand should be fair, but on the other hand should be close to book value, in order to create the lowest possible losses to the bank balance sheets.

Asked about the need to create a European bad bank, in an interview with Sole 24 Ore last June, Enria, now Chairman of the ECB Supervisory Board, said: “It is too early to talk about this. I remain convinced that the interventions made in Germany, Slovenia, Ireland, Spain after the 2008 crisis have been particularly effective in enabling faster and more effective cleaning of banks’ balance sheets. Incidentally, if well managed, bad banks do not produce losses. On the contrary, they even make profits. Everything depends on how the crisis develops. Let’s hope there is no need for it”.

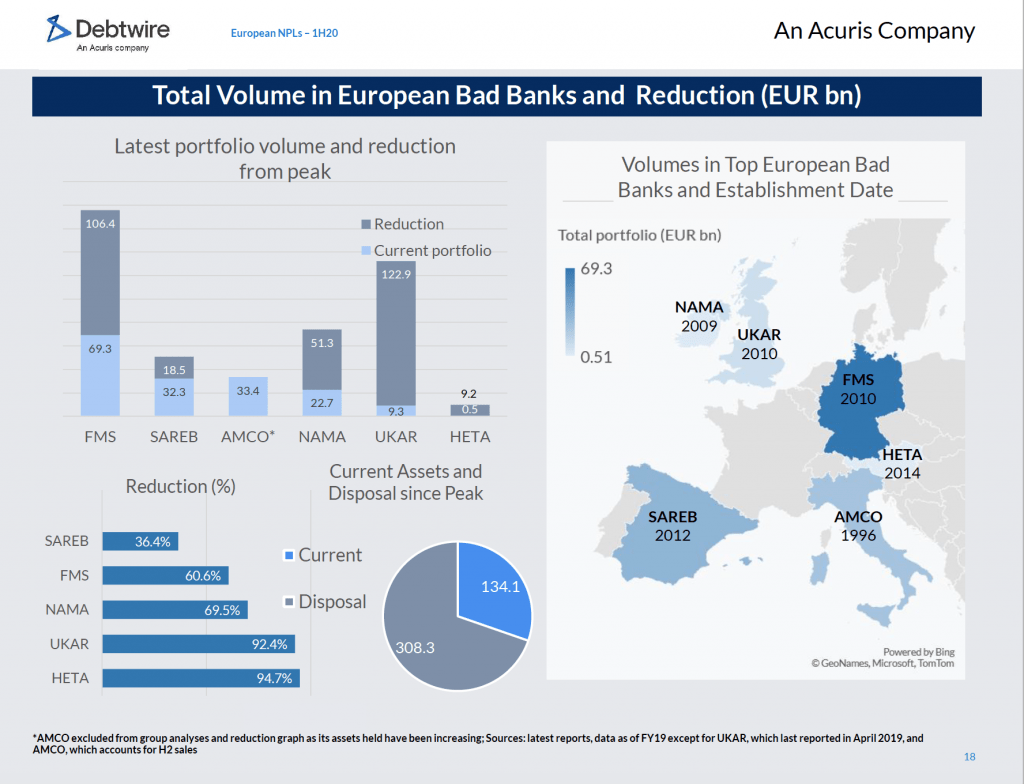

To date, some of the national bad banks set up following the 2008 crisis have almost exhausted their NPL portfolios. In particular, Debtwire calculated in its latest NPL Report, which BeBeez partly anticipated at the beginning of August (see other article by BeBeez), that the UK Asset Resolution (UKAR), created in 2010, sold most of its assets, which fell by £115.8 billion (€112.9 billion) to £8 billion (€9.3 billion). The FMS, founded by the German government in 2010, sold 106.4 billion euros in assets, but still has 69.3 billion euros in its portfolio. Spain’s SAREB still has 32.3 billion in assets in its portfolio, down from 50.8 billion when it was founded in 2013. Ireland’s NAMA, created in 2009, fully repaid the 31.8 billion euros of debt issued to purchase loans from banks in March 2020. In this context, the Italian AMCO is an outsider because it is still buying credits.

Returning to the issue of whether or not a European bad bank is needed, at the end of July the ECB published the results of a study on the impact of the crisis on the balance sheets of EU banks, assuming two different scenarios: one of a smaller recession in 2020 (-8.7% GDP) and a faster recovery in 2021 (+5.2% GDP) and 2022 (+3.3% GDP) and another of a more severe recession (GDP -12.6% in 2020, + 3.3% in 2021 and + 3.8% in 2022). The result of the year was that in the first case the average Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio of EU banks would deteriorate by only 1.9 percentage points, from 14.5% to 12.6%, and that banks would therefore be able to continue to play their role as financiers supporting the economy. In the event of a more severe recession, the worsening of CET1 would be 5.7 percentage points, down from 14.5% to 8.8%, which would require capital intervention by banks. If the latter scenario were to occur, commented Enria, “the authorities should be ready to implement further measures to prevent simultaneous deleveraging by banks, which could aggravate the recession and severely affect the quality of their assets”.

In any case, in the meantime, European banks are preparing for a new wave of impaired loans as a result of the Covid crisis. In the first quarter of the year, in fact, the main European banks set aside more than 21.5 billion euros to cover loan impairment losses, a figure that is equal to 207% of the 7 billion euros set aside at the end of the first quarter of 2019. This was also calculated by Debtwire in its latest NPL Report, which BeBeez anticipated at the beginning of August (see other article by BeBeez).

The largest percentage increase was recorded for banks in the UK and the DACH area (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) with a 450% increase from the same period last year. In particular, UK banks set aside 7.7 billion euros, with HSBC and Barclays alone providing coverage of 2.7 billion and 2.4 billion, respectively. The largest cover was provided by the Spanish Santander Group (3.9 billion), with the four largest Spanish banks providing a total of 6.2 billion, up 140% since 2019.

UniCredit provided coverage of 1.2 billion, of which 900 million related to potential losses due to the Covid-19 emergency. Greek banks provided a total of 1.4 billion in hedges, of which 860 million related to Covid.